FFA

Future Farmers of America

Inspired by the 1917 Smith-Hughes Vocational Education Act, Future Farmers of America (FFA) was established in 1928 in Kansas City, Missouri, as a club for white boys enrolled in agriculture classes. Additionally, in a major 1930 FFA organizational decision, females were officially banned from membership.

(Neosho Daily Democrat, 1928)

FFA Founding Meeting (National FFA Organization, 1928)

New Farmers of America

At the same time, New Farmers of America was created as a separate agricultural education program for black students who were excluded from FFA membership. NFA held their first national convention in Tuskegee, Alabama, and successfully earned recognition from the U.S. Department of Education.

NFA Emblem (A Chronology of NFA)

FFA Emblem (Official Manual for Future Farmers of America, 1952)

(Special Collections at IUPUI)

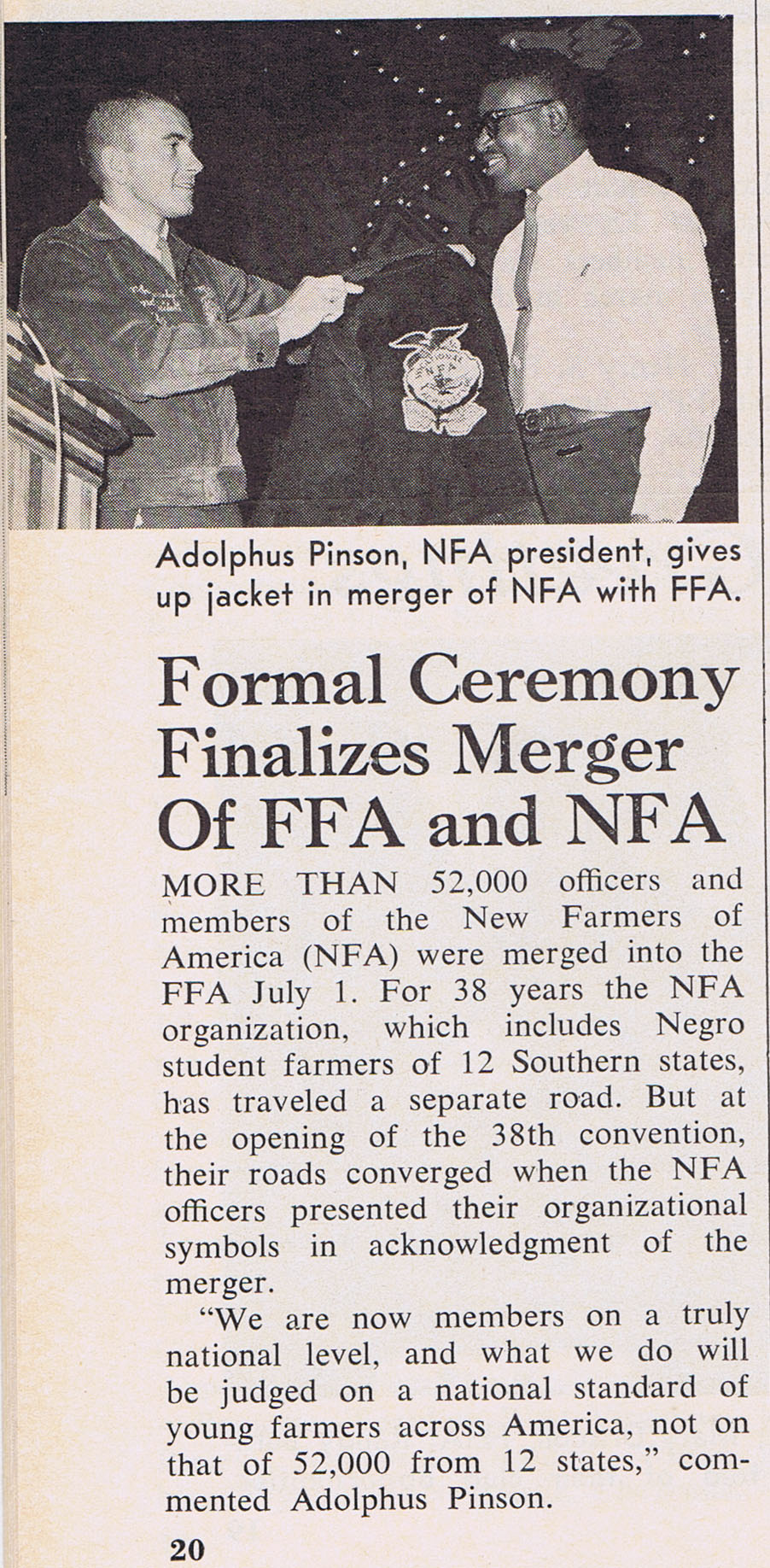

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Future Farmers of America was incentivized to merge with New Farmers of America. To ensure they wouldn’t be sidelined, multiple resolutions were presented at the 1965 meeting regarding constitutional changes, representation, reimbursement, and legal review. Even though the resolutions were ignored, the organizations still merged, which provided African American members with hope for a better future.

Concurrently, New Homemakers of America, a black organization, merged with Future Homemakers of America, allowing female students of all races to join FHA, the female counterpart to FFA.

FHA and Chapter Sweethearts

While Future Homemakers of America (FHA) was a home and family-based organization that taught young women how to be good wives and mothers, it didn't suit the needs of girls who wanted the opportunities FFA offered through contests and unique leadership positions that developed students’ agricultural and social skills.

FFA president and FFA sweetheart (National FFA Organization, 1954)

Sweetheart jacket vs. corduroy jacket (National FFA Organization)

However, while females couldn’t officially join Future Farmers of America, they could have limited involvement. In 1949, women were allowed to be FFA social ambassadors called Chapter Sweethearts and were given a white corduroy jacket. Though some considered this adequate, many were unsatisfied with their lack of membership.

"Who would deny that a pretty young lass as chapter sweetheart does much to help make FFA members proud of their chapter...It encourages boys to improve their social graces and become more competent in social situations...Her presence will add to the publicity value of many events…Be sure that the press is invited to functions where the sweetheart will appear."

(Cardozier, Public Relations for Vocational Agriculture: A Guide for Teachers, 1958, pp. 131-132)

Local Inclusion

Some local chapters allowed female members, although they were prohibited from national membership. While Dorothy Gilson of Pennsylvania successfully joined as a member in 1942, it was only because she registered as D. Gilson to hide her gender. In fact, the national organization deterred female inclusion through banning offending chapters from attending contests and national conventions. Additionally, females weren't allowed to wear official FFA jackets, as they weren't technically members.